Other relevant keywords: Political Cycles, Slavophile, Weimar Russia

Alexander Yanov (1930–2022)

Alexander Lvovich Yanov, a distinguished Russian-American political thinker and historian of Russian nationalism, began his academic journey at the Department of History at Moscow University, where he graduated in 1953. In 1970, he defended a dissertation on the history of Russian nationalism, entitled “The Slavophiles and Konstantin Leontiev” (“Slavianofily i Konstantin Leont’ev”). In the USSR Yanov was known as a publicist and literary critic, and his articles appeared in numerous Soviet journals. He also wrote a 2000-page book, History of Political Opposition in Russia (Istoriia politicheskoi oppozitsii v Rossii), which was widely distributed in Samizdat. His emigration to the United States in 1974 significantly influenced his career, leading to academic positions in political science at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor and the City University of New York, where he taught courses on Soviet politics and Russian history. Yanov’s emigration also facilitated the publication of his influential twenty-four books in four languages, including The Russian Challenge and the Year 2000 (1987), a work that has left a lasting impact on the study of Russian political history.

History of Russia and the Slavophile-Westernizer Debate

Alexander Yanov was a neo-westernizer, a successor to the centuries-old tradition of Russian intellectual debates between the Westernizers and the Slavophiles. This ideological polarization began in the first half of the nineteenth century. Both camps agreed that Russian statehood originated as a successor to the authoritarian rule of the Mongol Golden Horde, but they strongly disagreed on the merits of such a succession and the future of the Russian state and culture. The Westernizers aimed to make Russia a European country and supported the reforms of Peter the Great (1672–1725), who modernized Moscovite Rus by “cutting a window to Europe.” They stood for the Constitution and the limitation of the monarch’s power. The Slavophiles, in turn, blamed Peter for betraying “the lore of ages long gone by, / In hoar antiquity compounded” by introducing elements of foreign cultures that were incompatible with Russian national life (Pushkin 131). The Slavophiles likewise insisted on personal spiritual freedom and independence, which they argued Peter had eliminated by subordinating the hierarchy of the Orthodox Church to tight governmental control.

In his magnum opus, the trilogy Russia and Europe (Rossiia i Evropa, 2007–2009), Yanov challenged the long-accepted narrative by both parties that Russian statehood had originated in authoritarian rule, be it from the Mongol khans or Byzantine emperors. He proposed a new paradigm of Russian political history, asserting that from its beginnings in Kyivan Rus, Russia has contained two polarizing traditions—one European and contractual, and the other paternalistic and servile. In the first volume of his trilogy, Russia’s European Century (Rossiia i Evropa, 2007), Yanov writes:

No one, as far as I know, disputes that at the beginning of the second Christian millennium, the Kievan-Novgorod conglomerate of Vikings’ princedoms and Veche towns were perceived in the world as quite a European community … The only problem is that Russia, especially after the death of Yaroslav the Wise in 1054, was, albeit a European one, [an unviable] proto-state. (28–29)

According to the “ruling stereotype of world historiography,” Yanov continues, “Russia emerged from the [following Mongol] yoke … as an heir, not of her historical predecessor, European Russia, but of the alien Mongol Horde.” In other words, “European Rus turned into the Asian-Byzantine Muscovy” (28–29).

In contrast to prevailing opinions, Yanov shows in this volume that “Russia began its historical path in the 1480s [as] an ordinary North European state, little different from Denmark or Sweden, and in political terms much more progressive than Lithuania or Prussia” (Rossiia i Evropa 34). Based on new archival discoveries by Russian-Soviet historians of the 1960s, he demonstrates that “Moscow was the first in Europe to embark on the ecclesiastical Reformation and the first among the great European powers to try to become a constitutional monarchy. Not to mention that in the middle of the 16th century, it was able to create quite European local self-government and the Collection of Laws of 1550, which [may be considered] a Russian version of the Magna Carta” (35). However, Yanov argues that the historical tragedy of Russia consisted in the immediate and consequential failure of those reforms. “The struggle for the ecclesiastical Reformation,” Yanov continues, “ended in Russia, unlike its northern European neighbors, with a crushing defeat for the state” (35). He notes that the same fate has befallen the “constitutional aspirations of the boyar reformers of the 16th–17th centuries. Local self-government and jury trials perished in the fire of the autocratic revolution of Ivan the Terrible” (35).

Ever since, Yanov writes, “Russia has carried within its political trajectory an ever-swinging pendulum, the deadly confrontation of two irreconcilable and equal-in-strength traditions—of arbitrary rule and safeguards” (37). Yanov concludes:

It is impossible to imagine these two European and paternalistic trees having grown from the same root … Their coexistence in one country can be explained only on one condition—namely if we assume that Russia has not one but two equally ancient and legitimate political traditions. The European one (with its guarantees against arbitrary power, constitutional limitations, political tolerance, and rejection of state paternalism). And the paternalistic one (with its proclamation of Russia’s exceptionalism, state ideology, dream of superpower, and ‘messianic greatness and vocation’). (35)

Yanov argues that, beginning in the sixteenth century, any attempt at Russia’s transformation in the direction of Europe has ended in political stagnation or was turned backward by counter-reform.

Political Cycles

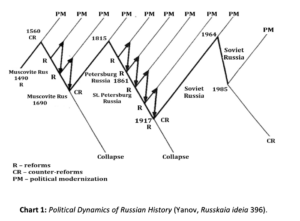

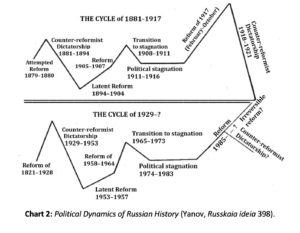

According to Yanov, Russian political history over the past five hundred years has followed a pattern of historical repetition, in which Russia has failed to promote political and economic reforms that would enable it to become a Western-style, non-authoritarian country. In its abstract form, the “Yanov cycle” begins with “counter-reforms,” which aim to halt progressive developments and return the country to its authoritarian track. A violent and repressive dictatorship is later replaced by structural reforms that soften the regime but retain the system intact. The third stage of the cycle is political and economic stagnation. Finally, when the system is no longer sustainable, there comes the time for systemic reforms, which fail and give way to dictatorial measures once again.

At a general level, Yanov’s cycle mirrors the rotation of the four seasons: after the freezing winter of tyranny comes the thaw of reforms. The relative stability of stagnation at the cycle’s peak is followed by more decisive reforms, which, in turn, signal the approaching fall, ultimately leading to the disintegration of the system. More specifically, Yanov distinguishes seven dictatorial regimes that turned the wheel of another political cycle in Russia. These are the dictatorships of Ivan the Terrible (1560–1584), Peter the Great (1689–1725), Pavel I and Alexander I (1796–1881), Nicholas I (1825–1855), Alexander III (1881–1894), Vladimir Lenin (1918–1921), and Joseph Stalin (1929–1953). Correspondingly, the 1550s, 1680s, 1825, 1879–1880, 1917, and 1920 reforms were reversed by counter-reforms, while the reforms of 1605–1610, the 1720s, 1760s, 1800s, 1860s, 1905–1907, and 1960 dissolved into stagnation.

Yanov’s understanding of the Russian historical cycle as a continuous struggle between reforms and counter-reforms allows him to reconsider many well-known facts of Russian history. For instance, he analyzes various political models, such as Muscovite Rus, the St. Petersburg Empire, and Soviet Russia, alongside the ideologies they represent, as different manifestations of essentially the same historical phenomenon. He draws parallels between Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and Joseph Stalin, noting that these autocrats led the Russian state during periods of counter-reform.

Weimar Russia

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia embarked on yet another attempt at democratic reform. In his 1995 work, After Yeltsin: “Weimar” Russia (Posle Eltsina. “Veimarskaia” Rossiia), Yanov introduces his notion of “Weimar Russia,” drawing an analogy with the period that brought Hitler to power and challenged the West. This “Weimar” period in Russia’s history, as Yanov described it, could either break the cycle or plunge the country into another counter-reform, one that risked turning it into a fascist nuclear superpower. Subsequently, in his book The History of One Renunciation (2012), Alexander Yanov radically changed his position. After this work, he rescinded his view that “Russia of the 1990s was ‘Weimarized’ [or] that it is being ‘Weimarized’ now,” by which he meant the 2010s.

Yanov’s argument about contemporary Russia can be boiled down to the following. First, he noted that the “patriotic hysteria” of the Putin era was not new to Russian history and would not necessarily lead to fascism. Second, he argued that the ideology of ultranationalism could not prevail in a multi-ethnic and multi-religious country like Russia. Thirdly, he noted that post-Soviet Russia, unlike Hitler’s Germany, was unable to provide its citizens with economic prosperity at the European level. And, finally, Yanov argued that in Russia there is no charismatic leader on the horizon who might proclaim “to the whole world, like his predecessor, something like this: ‘Either Germany will be a world power again, or there will be no Germany at all'” (Yanov, “Istoriia odnogo otrecheniia”).

As it turned out, Alexander Yanov renounced his scholarly prediction prematurely. In the end, the existential nightmare of “Weimar Russia,” which had for many years haunted and horrified him, nevertheless materialized: the “coming to power in Moscow … of an aggressive dictatorship, as unpredictable as today’s Iran, and as isolated from the world as North Korea but controlling, unlike them, mountains of nuclear weapons,” as Yanov described it in 2012 (“Istoriia odnogo otrecheniia”). On February 24, 2022, less than a week after Alexander Yanov’s death, Russia unleashed a full-scale invasion against neighboring Ukraine.

Despite changes in his views on fascism in Russia, Yanov was blunt in his assessment of Putin’s actions and initiatives. He maintained that by changing the Russian Constitution and intensifying repressions in the early 2020s, the Russian president was digging the grave of his authoritarian regime (Yanov, “Pro ‘vechnoe’ samoderzhavie” 28). No matter how mighty and impregnable autocratic power in Russia may seem, for Yanov there will always come a moment when its Western origins and aspirations are revealed, and with renewed vigor, leading to ever more comprehensive reforms. Yanov remained confident that after centuries of historical tossing and autocratic backsliding, Russia would eventually become a Western country.

Mikhail Sergeev, October 2024

Bibliography

Pushkin, Alexander. Ruslan and Liudmila. Collected Narrative and Lyrical Poetry. Edited and translated by Walter Arndt. Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1989.

Yanov, Alexander L. “Istoriia odnogo otrecheniia. Pochemu v Rossii ne budet fashizma.” Snob, December 15, 2011. https://snob.ru/selected/entry/44335/.

—. Posle Eltsina. “Veimarskaia” Rossiia. Moscow: Krook, 1995.

—.”Pro ‘vechnoe’ samoderzhavie.” In Russkoe Zarubezh’e: Antologiia sovremennoi filosofskoi mysli, edited by M. Sergeev. Moscow: M-Grafiks, 2018.

—. Rossiia i Evropa v trekh knigakh. Moscow: Novyi Khronograf, 2007–2009.

—. Russkaia ideia. Ot Nikolaia I do Putina. 4 vols. Moscow: Novyi Khronograf, 2014–16.

—. Russkaia ideia i 2000 god. New York: Liberty Publishing, 1988.

—. The Russian Challenge. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1987.